How producer and engineer Adam Moseley built a legacy that started at London’s legendary Trident Studios to working with today’s hardware and plugins

When Adam Moseley showed up for his job interview at the original Trident Studios in London in 1978, he didn’t know anything about audio engineering. After several “really awful failed attempts” at playing in bands during school, he knew he wasn’t cut out for performing. As a child, Moseley remembered admiring the credits on the albums his father and older sister used to play—and he set out to add his name to these ranks.

“My dad was a jazz musician, and he’d always bring home vinyl,” says Moseley, who grew up in Brighton, England. “One of the first things I learned to read was ‘producer’ on the back of the cover. That was the biggest name in the credits, and I realized he must be the guy who knew how to make records. So, I thought, that’s what I’ll do: I’ll get a job in a studio as a producer.”

As a mixer, engineer, and producer, Moseley has carved out a successful career working with multi-platinum artists like The Cure, U2, Beck, Rush, and Kiss, Nikka Costa with Lenny Kravitz and Prince while making a mark on film and TV series like “True Blood,” “The Americans,” and Spike Jonze’s “I’m Here.” While traveling halfway around the world crafting his sonic signature across several decades and genres of music, Moseley hasn’t strayed far from his Trident roots.

Making the cut

After one year of law school in London, Moseley started sending letters to every studio he could find, trying to land an interview. After reviewing his resume, Trident’s manager saw a perfect fit for him: assisting the construction crews by day to enlarge the window and control room for the Trident A-Range console, and cooking three-course meals for the studio’s staff by night. While it wasn’t quite the producer gig he dreamed of, it was a foot in the door.

After three months of working double-duty from 9 a.m. to 3 a.m., Moseley was promoted to the role of “teaboy,” delivering tea and coffee during sessions and running odd errands for the studio staff. Over time, Trident’s team began “to mold him in their likeness” as he worked his way up the ranks.

“That was very much the Trident method,” he explains. “You had to work your way up from teaboy to tape op, senior tape op to assistant engineer, then engineer. If you didn’t screw up as a teaboy, then you’d move on to assist in the mastering room, starting to be a tape op, an assistant engineer, getting involved on the desk, and then making it to engineer.”

The competition was fierce at every stage. Moseley says Trident usually employed an extra person at every level to allow frequent firings of those who didn’t make the cut. “Almost every month, someone got fired,” he says, “so you were always on your toes. It was grueling. Trident really pushed the upcoming engineers to represent the high standards of the Trident name.”

Learning the Trident way

Back then, Moseley says, each studio had its own method of training aspiring engineers. Abbey Road Studios, for example, was quite rigid in its approach. “The engineers had to wear jackets and ties, and they weren’t allowed to touch the mics,” he says. “The techs would come in wearing their white lab coats and position the mics in the official Abbey Road way. Geoff Emerick, the legendary Beatles engineer, shared that he nearly got fired several times for moving mics.”

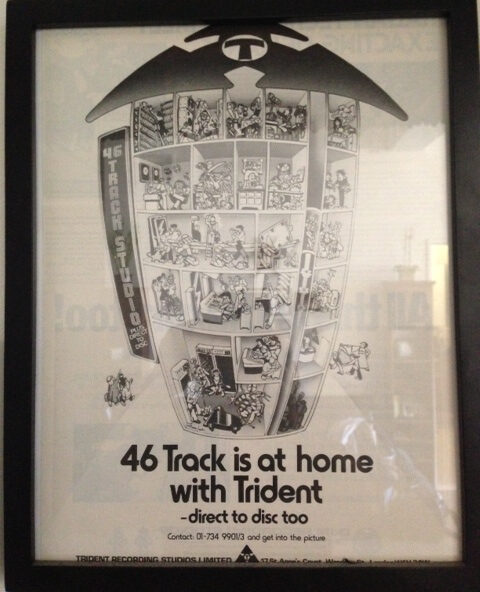

Trident, meanwhile, was much more “experimental,” he says, “in every way that word could mean in the 70s.” The studio was on the cutting edge of new technologies, as the first in the UK to record on 8-track, then 16, 24, and 48—which they cleverly marketed as 46-track, since one track on each reel was reserved for code to synchronize the two, leaving 46 recordable tracks.

That innovative, experimental approach was what lured the Beatles away from Abbey Road to record several tracks for their legendary self-titled White Album at Trident, including “Hey Jude” and “Martha My Dear.” Not only did the extra tracks allow them more room for overdubbing, Moseley says, “but also it was freer and less restricted than Abbey Road.”

Following the Fab Four’s lead, a bevy of influential artists recorded landmark albums at Trident Studios in the early 70s—David Bowie made “Space Oddity,” “Hunky Dory,” and “Ziggy Stardust,” Marc Bolan brought T. Rex to life, Elton John came onto the scene, Genesis began making hits, Lou Reed recorded “Transformer,” and other iconic artists like Carly Simon, Harry Nilsson, John and Yoko, George Harrison, Peter Gabriel, and many more joined the ranks.

Paul McCartney even brought a young, aspiring guitarist friend to Trident, scoring the unknown band free demo time during the studio’s off-hours in the early morning. That band was Queen, and went on to to sign to Trident and record its first five albums there, with Trident’s owner, Norman Sheffield, as their manager.

The engineers and producers who made those epic albums—guys like Ken Scott, Tony Visconti, Roy Thomas Baker, Dave Hentschel, John Anthony, and Gus Dudgeon, —became the “forefathers of the Trident way.” For several years, Moseley worked closely under the wing of Mike Stone, who also started out as a teaboy then worked his way up to tape op/assistant just before Queen came into the studio in 1972. Since no one else wanted to cut demos at 2 a.m., the task fell on Stone—who went on to become the band’s acclaimed engineer.

“No one ever sat me down and taught me anything, at least not in the traditional sense,” says Moseley, who cut his chops assisting Stone to engineer solo albums for all four members of Kiss. “I’d be assisting Mike and he’d say, ‘Patch the 1176 compressor on the bass. Put the LA-2A’s on the acoustics, and LA-3A’s on the saturated guitars.’ I was never taught why, but I wasn’t going to question or doubt the guy who made the Queen records that changed my life.” Stone, in turn, learned from the guys who made the Beatles and Bowie albums. Peter Kelsey and Stephen W. Tayler were two other Trident engineers who greatly influenced and educated Moseley.”

After sessions ended, Moseley tinkered with the gear to understand why Stone asked for certain settings. Through keen observation, trial, and error, Moseley slowly trained his ears to hear the nuanced differences each piece of equipment produced.

Meeting Trident’s standards

After Trident introduced the original A-Range console in 1971 and the B-Range in 1973, the Fleximix came out in 1979. Designed specifically for Queen to take on the road, the live sound console often served as a secondary mixing desk in the studio, adding more inputs beyond the 40 tracks on the Series B.

“As a tape op assistant, your first jobs would be on the Fleximix behind the main desk,” Moseley explains. “I felt like the 16-year-old at the family wedding, where you have to sit at the kiddie table looking at your other cousins who made it to the grownup table. But if you didn’t screw up that one move in a mix, you’d be given more duties, and eventually you got to sit with the grownups—the star producer and band members—at the big desk.”

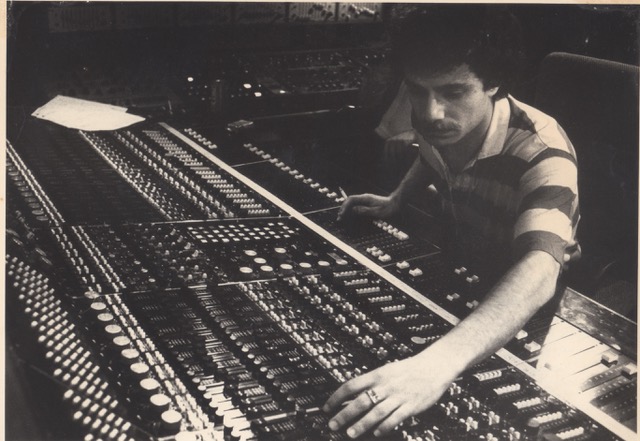

Moseley’s first chance to sit at the B-Range with the “grownups” was for Rush’s “Permanent Waves” album in 1979. As assistant engineer, he says, “I had 10 faders, and then Terry Brown, the producer, was next to me with 10 faders—all squashed up shoulder-to-shoulder—with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson next to him, the four of us mixing, live, in edits, bit by bit.”

The ultimate test of Moseley’s recording competence came during his first session as an engineer. Six hours into the session, the studio manager and chief engineer walked in and asked the band and producer to leave the room so they could have a moment with Moseley. “I thought, ‘Oh shit, what have I done?’” Moseley remembers. “Then, the studio manager asked to hear my drums, because the drum sound at Trident was a badge of honor that had to be earned. That was a defining moment, and if I hadn’t been worthy of the Trident drum sound, I’d have been out the door.”

Obviously, he nailed it—or you wouldn’t be reading this now. He went on to work with Yes drummer, Bill Bruford, on seven albums, from teaboy to engineer to producer.

To this day, Moseley says, the pressure of that drum test still drives his high sonic expectations for every project. “The weight of that legacy has never left me,” he says. “I am still aware of that Trident manager standing behind me, and I want to be sure that what I’m doing is of the standard that I learned and worthy of my heritage.”

Reviving Trident’s second era

Moseley worked at Trident Studios from January 1978 until it closed in November 1981. Then, he left for New York, where he worked at Sorcerer Sound and Park South Studios.

“Stepping out of Trident was terrifying because it was the only studio I’d ever been in,” he recalls. “Suddenly going out and working on a different console, after I was so used to the Trident A-Range, was disorienting. I’d turn up a frequency to where I thought it should be, but the sonics were completely different. I didn’t have the enormous Cadac mix room speakers either. It was like someone pulled the rug out from under my feet. It really rocked my confidence.”

Then, in 1983, Trident reopened under new ownership, and they asked Moseley to come back and head a team of engineers worthy of the studio’s sequel. His all-star team at this second legendary era of Trident included:

- Mark “Flood” Ellis, who went on to record several U2 albums, along with Depeche Mode and Nick Cave.

- Alan Moulder, later known for his work with the Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, and The Killers.

- Mark “Spike” Stent, who later won several Grammys for his work with Madonna, Beyonce, Muse, and more.

- Steve Osborne, who produced KT Tunstall and helped Paul Oakenfold mix dance music that defined the club scene

- Al Clay, who eventually left to partner with the studio’s “go-to keyboard synth guy, Hans Zimmer,” working on major movie scores for “Pirates of the Caribbean,” “Batman Begins,” and a host of other films.

Moseley is also credited as one of the engineers on The Buggles’ major hit, “Video Killed the Radio Star,” which was the song that launched MTV, with keyboards by Zimmer.

Over the next 15 months, Moseley only got three weekends off—as he and Trident 2 were both in high demand. Meanwhile, the equipment continued to evolve, as Trident Audio Developments (the manufacturing offshoot of the original studio) continued to innovate new consoles.

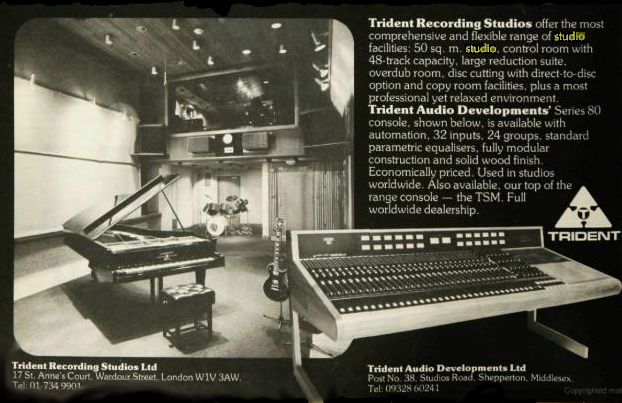

After selling the original A-Range and B-Range consoles from the studio, the owners of Trident 2 wanted to replace them with the Series 80B, released in 1983. But Moseley wanted to make a few modifications first.

“I wanted them to cut it in half, and in the middle of the console, put 24 EQ modules from the TSM, which were the sliding fader EQs like the A-Range had,” he says. “I wanted to keep that Trident depth of EQ in this new console, because that was the sound I measured every mix against.”

While the 80B consoles lent a definitive “bright, punchy 80s sound” that shaped the New Wave music of the era, Moseley still credits the original A-Range with his biggest musical breakthroughs.

“The last two records I did on the A-Range at Trident were two of the biggest records I ever did,” says Moseley, of The Cure’s 1985 single, “Close to Me,” and the Blow Monkeys’ 1986 single, “Digging Your Scene,” which was a worldwide hit and his first official credit as producer. “Those were the two records that shaped my career, so the A-Range is always special to me.”

Moseley went on to produce hits with Roxette, Richard Marx, Maxi Priest, and many other famous artists. He worked on records with Bowie’s guitarist Mick Ronson, Beck with Jack White, The Sex Pistols, Nico, Wolfmother, Nikka Costa with Lenny Kravitz and Prince, and he collaborated with The Velvet Underground’s John Cale on several albums and films

New tools, classic sound

Perhaps those milestone projects explain why Moseley still strives to achieve the signature A-Range warmth in his work today.

“The Trident A-Range was the most defined EQ you could get. You could create sounds through the EQ that other vintage consoles can’t; you will just not get the same punch,” he says. “The sound of that Trident A-Range console has always been my reference point. When I’m wondering if I’ve got enough warmth, if the sound is tight enough, or if I’ve got enough punch, my approach is influenced by my time at Trident. Those formative four years on the A-Range inherently determine how I hear and manipulate sound.”

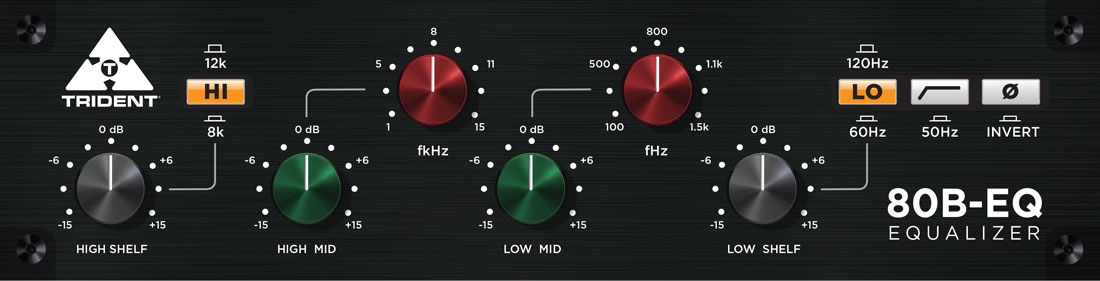

The difference is that today, he uses a suite of digital tools to achieve those classic sounds. These days, Moseley mixes almost entirely in the box. Whether he records directly through his Trident Series 80B outboard gear or applies the 80B EQ and CB 9066 EQ plugins to other recordings, Moseley can inject the classic Trident sound into anything he mixes.

“If I’m mixing and I want to make it sound like it was recorded on a Trident console, I’ll use the plugins to get back that character and depth of sound. They are perfect and very true to the original consoles” he says.

For example, when he’s mixing piano parts, Moseley can’t help but think of the legendary Bechstein piano at Trident, known for lending its distinctive sound to hits like Elton John’s “Your Song,” The Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” Queen’s “Killer Queen,” and Bowie’s “Life On Mars.” “If I’m working on a song with piano, I have to use a Trident EQ plugin,” he says. “Otherwise, I’m not going to be able to manipulate the frequency to get the sound I want.”

Sonic shape-shifting

Mixing, from Moseley’s perspective, is a multidimensional experience. The first time he listens to a song before he begins mixing, he maps out an audio visual “drawing” in his head.

“In my mind, I visualize a drawing of the shapes, colors, and positions of the sounds and the perspective of where they are in the eventual mix and how they move,” he says. “That gives me a clear blueprint of where I want the production and mix to go. I love taking a sound and bringing it forward to let it do its thing, and then letting it slip away to make room for something else. It’s what I experienced and learned in my first mixing sessions with Rush.”

Moseley likens this sonic trick to a magician’s sleight of hand. By sculpting sounds through Trident’s defined EQ, he says, he can manipulate where the listener’s attention goes—maximizing the auditory impact of his mixes. He refers to this phenomenon as shape-shifting, a concept spawned from the dynamic approach to mixing he learned at Trident.

“I used to love listening to my mixing projects from behind the console, leaning over between the speakers. You’d get a very immersive, surround-sound kind of feeling,” he says. “That inspired my concept of mixing using the space above, below, and all around the speakers. You’ve got this whole world of depth and perspective and placement of sound.”

This spatial mixing method gave Moseley a reputation for making immersive, cinematic mixes—which naturally paved his way to mixing TV themes and film scores about 15 years ago. Since then, Moseley has mixed music for shows like HBO’s “True Blood,” “The Americans” on FX, and AMC’s “The Son.” He broke into the movie scene working on flicks like “Smokin’ Aces,” “The Big Wedding,” and several Spike Jonze titles, including “Where the Wild Things Are” and a short film called “I’m Here.”

“Normally, when I’m working on a score, the movie is finished. But we had to start the score for that short the same day that Spike Jonze started filming,” says Moseley, who made the score with Nick Zinner from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. “We didn’t have any visuals, so during the day, Spike Jonze would run into the control room during his breaks to show us characters and locations on his digital camera and then we would proceed to create music that ‘felt’ like the characters. It was fascinating.”

Sharing the legacy

Now, four decades since the original Trident Studios closed, Moseley recognizes that it wasn’t just technical engineering skills he learned there, but all-around music business etiquette.

“I’m amazed at how strongly my first four years have directed the rest of my 45 year career,” Moseley says, “in terms of learning how producers work with artists, how to run a session, how to talk to people, how not to talk to people, how to keep the budget and schedule on track, how to keep the flow going and, importantly, how to deliver.”

Today, Moseley puts all these Trident lessons intro practice running Accidental Entertainment, his independent synch-licensing and publishing company with about 120 artists on its roster. He also operates Accidental Studios out of his house in Silver Lake, just minutes from Hollywood. As CEO and head of A&R, Moseley finds joy in nurturing young stars to help grow their careers.

Meanwhile, Moseley also passes down these lessons to the music production students he teaches at UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. In fact, most of his employees were former students who entered his internship program and eventually got hired. With seven employees currently on his staff, Accidental Entertainment is poised to double in size as his roster and company expand.

“I love sharing my knowledge and teaching—hopefully inspiring—young music makers,” says Moseley, who has taught at UCLA since 2016 and also at Berklee College of Music in Valencia, Spain. “With studios disappearing and a lot of engineers my age leaving the planet, there’s a wealth of knowledge that can be shared in a very relevant, modern way. I bring in the old-school methods and show them how to manipulate sound with today’s tools. I have been very active with Trident plugins, Barefoot speakers, and Plugin Alliance.”

Whether he’s teaching students or mentoring artists, Moseley is culminating his Trident training with decades of industry experience to shape the next generation of music makers. Being raised in the Trident way, he’s working to preserve the legendary legacy as producing, recording, and mixing methods continue to evolve.

“It always comes back around to Trident,” he says. “Those lessons and methods have thankfully carried through my whole career.”